Text Mining

What is Text Mining?

- Use of computational techniques to extract high-quality information from text

- Extract and discover knowledge hidden in text automatically

- KDD definition: “discovery by computer of new previously unknown information, by automatically extracting information from a usually large amount of different unstructured textual resources”

Text Mining Categories

- Document Categorization (Supervised Learning)

- Document Clustering/Organization (Unsupervised Learning)

- Summarization (keywords, indices, etc)

- Visualization (word cloud, maps)

Numeric prediction (stock market prediction based on news text)

Examples

- Text mining is an exercise to gain knowledge from stores of language text.

- Text:

- Web pages

- Medical records

- Customer surveys

- Email filtering (spam)

- DNA sequences

- Incident reports

- Drug interaction reports

- News stories (e.g. predict stock movement)

- Typical Applications for Text Mining

- Unstructured text is very common, and in fact, may represent the majority of information available to a particular research or data mining project.

- Analyzing open-ended survey responses.In survey research (e.g., marketing), it is not uncommon to include various open-ended questions pertaining to the topic under investigation. The idea is to permit respondents to express their “views” or opinions without constraining them to particular dimensions or a particular response format. This may yield insights into customers’ views and opinions that might otherwise not be discovered when relying solely on structured questionnaires designed by “experts.” For example, you may discover a certain set of words or terms that are commonly used by respondents to describe the pro’s and con’s of a product or service (under investigation), suggesting common misconceptions or confusion regarding the items in the study.

- Automatic processing of messages, emails, etc.Another common application for text mining is to aid in the automatic classification of texts. For example, it is possible to “filter” out automatically most undesirable “junk email” based on certain terms or words that are not likely to appear in legitimate messages, but instead identify undesirable electronic mail. In this manner, such messages can automatically be discarded. Such automatic systems for classifying electronic messages can also be useful in applications where messages need to be routed (automatically) to the most appropriate department or agency; e.g., email messages with complaints or petitions to a municipal authority are automatically routed to the appropriate departments; at the same time, the emails are screened for inappropriate or obscene messages, which are automatically returned to the sender with a request to remove the offending words or content.

- Analyzing warranty or insurance claims, diagnostic interviews, etc.In some business domains, the majority of information is collected in open-ended, textual form. For example, warranty claims or initial medical (patient) interviews can be summarized in brief narratives, or when you take your automobile to a service station for repairs, typically, the attendant will write some notes about the problems that you report and what you believe needs to be fixed. Increasingly, those notes are collected electronically, so those types of narratives are readily available for input into text mining algorithms. This information can then be usefully exploited to, for example, identify common clusters of problems and complaints on certain automobiles, etc. Likewise, in the medical field, open-ended descriptions by patients of their own symptoms might yield useful clues for the actual medical diagnosis.

- Investigating competitors by crawling their websites.Another type of potentially very useful application is to automatically process the contents of Web pages in a particular domain. For example, you could go to a Web page, and begin “crawling” the links you find there to process all Web pages that are referenced. In this manner, you could automatically derive a list of terms and documents available at that site, and hence quickly determine the most important terms and features that are described. It is easy to see how these capabilities could efficiently deliver valuable business intelligence about the activities of competitors.

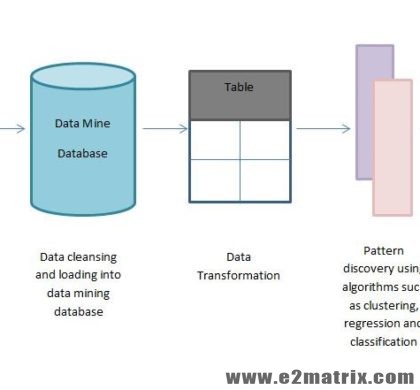

Approaches to Text Mining

To reiterate, text mining can be summarized as a process of “numericizing” text. At the simplest level, all words found in the input documents will be indexed and counted in order to compute a table of documents and words, i.e., a matrix of frequencies that enumerates the number of times that each word occurs in each document. This basic process can be further refined to exclude certain common words such as “the” and “a” (stop word lists) and to combine different grammatical forms of the same words such as “traveling,” “traveled,” “travel,” etc. (stemming). However, once a table of (unique) words (terms) by documents has been derived, all standard statistical and data mining techniques can be applied to derive dimensions or clusters of words or documents, or to identify “important” words or terms that best predict another outcome variable of interest.

Using well-tested methods and understanding the results of text mining. Once a data matrix has been computed from the input documents and words found in those documents, various well-known analytic techniques can be used for further processing those data including methods for clustering, factoring, or predictive data mining

“Black-box” approaches to text mining and extraction of concepts. There are text mining applications which offer “black-box” methods to extract “deep meaning” from documents with little human effort (to first read and understand those documents). These text mining applications rely on proprietary algorithms for presumably extracting “concepts” from text, and may even claim to be able to summarize large numbers of text documents automatically, retaining the core and most important meaning of those documents. While there are numerous algorithmic approaches to extracting “meaning from documents,” this type of technology is very much still in its infancy, and the aspiration to provide meaningful automated summaries of large numbers of documents may forever remain elusive. We urge skepticism when using such algorithms because 1) if it is not clear to the user how those algorithms work, it cannot possibly be clear how to interpret the results of those algorithms, and 2) the methods used in those programs are not open to scrutiny, for example by the academic community and peer review and, hence, we simply don’t know how well they might perform in different domains. As a final thought on this subject, you may consider this concrete example: Try the various automated translation services available via the Web that can translate entire paragraphs of text from one language into another. Then translate some text, even simple text, from your native language to some other language and back, and review the results. Almost every time, the attempt to translate even short sentences to other languages and back while retaining the original meaning of the sentence produces humorous rather than accurate results. This illustrates the difficulty of automatically interpreting the meaning of a text.

Text mining as document search. There is another type of application that is often described and referred to as “text mining” – the automatic search of large numbers of documents based on keywords or key phrases. This is the domain of, for example, the popular internet search engines that have been developed over the last decade to provide efficient access to Web pages with certain content. While this is obviously an important type of application with many uses in any organization that needs to search very large document repositories based on varying criteria, it is very different from what has been described here.

Issues and Considerations for “Numericizing” Text

Large numbers of small documents vs. small numbers of large documents. Examples of scenarios using large numbers of small or moderate-sized documents were given earlier (e.g., analyzing warranty or insurance claims, diagnostic interviews, etc.). On the other hand, if your intent is to extract “concepts” from only a few documents that are very large (e.g., two lengthy books), then statistical analyses are generally less powerful because the “number of cases” (documents) in this case is very small while the “number of variables” (extracted words) is very large.

Excluding certain characters, short words, numbers, etc. Excluding numbers, certain characters, or sequences of characters, or words that are shorter or longer than a certain number of letters can be done before the indexing of the input documents starts. You may also want to exclude “rare words,” defined as those that only occur in a small percentage of the processed documents.

Include lists, exclude lists (stop-words). The specific list of words to be indexed can be defined; this is useful when you want to search explicitly for particular words and classify the input documents based on the frequencies with which those words occur. Also, “stop-words,” i.e., terms that are to be excluded from the indexing can be defined. Typically, a default list of English stop words includes “the”, “a”, “of”, “since,” etc, i.e., words that are used in the respective language very frequently but communicate very little unique information about the contents of the document.

Synonyms and phrases. Synonyms, such as “sick” or “ill”, or words that are used in particular phrases where they denote unique meaning can be combined for indexing. For example, “Microsoft Windows” might be such a phrase, which is a specific reference to the computer operating system, but has nothing to do with the common use of the term “Windows” as it might, for example, be used in descriptions of home improvement projects.

Stemming algorithms. An important pre-processing step before indexing of input documents begins is the stemming of words. The term “stemming” refers to the reduction of words to their roots so that, for example, different grammatical forms or declinations of verbs are identified and indexed (counted) as the same word. For example, stemming will ensure that both “traveling” and “traveled” will be recognized by the text mining program as the same word.

Support for different languages. Stemming, synonyms, the letters that are permitted in words, etc. are highly language dependent operations. Therefore, support for different languages is important.

Transforming Word Frequencies

Once the input documents have been indexed and the initial word frequencies (by document) computed, a number of additional transformations can be performed to summarize and aggregate the information that was extracted.

Log-frequencies. First, various transformations of the frequency counts can be performed. The raw word or term frequencies generally reflect on how salient or important a word is in each document. Specifically, words that occur with greater frequency in a document are better descriptors of the contents of that document. However, it is not reasonable to assume that the word counts themselves are proportional to their importance as descriptors of the documents. For example, if a word occurs 1 time in document A, but 3 times in document B, then it is not necessarily reasonable to conclude that this word is 3 times as important a descriptor of document B as compared to document A. Thus, a common transformation of the raw word frequency counts (wf) is to compute:

f(wf) = 1+ log(wf), for wf > 0

This transformation will “dampen” the raw frequencies and how they will affect the results of subsequent computations.

Binary frequencies. Likewise, an even simpler transformation can be used that enumerates whether a term is used in a document; i.e.:

f(wf) = 1, for wf > 0

The resulting documents-by-words matrix will contain only 1s and 0s to indicate the presence or absence of the respective words. Again, this transformation will dampen the effect of the raw frequency counts on subsequent computations and analyses.

Inverse document frequencies. Another issue that you may want to consider more carefully and reflect in the indices used in further analyses are the relative document frequencies (df) of different words. For example, a term such as “guess” may occur frequently in all documents, while another term such as “software” may only occur in a few. The reason is that we might make “guesses” in various contexts, regardless of the specific topic, while “software” is a more semantically focused term that is only likely to occur in documents that deal with computer software. A common and very useful transformation that reflects both the specificity of words (document frequencies) as well as the overall frequencies of their occurrences (word frequencies) is the so-called inverse document frequency (for the i’th word and j’th document):

In this formula (see also formula 15.5 in Manning and Schütze, 2002), N is the total number of documents and defines the document frequency for the i‘th word (the number of documents that include this word). Hence, it can be seen that this formula includes both the dampening of the simple word frequencies via the log function (described above), and also includes a weighting factor that evaluates to 0 if the word occurs in all documents(log(N/N=1)=0), and to the maximum value when a word only occurs in a single document (log(N/1)=log(N)). It can easily be seen how this transformation will create indices that both reflect the relative frequencies of occurrences of words, as well as their semantic specificities over the documents included in the analysis.

Latent Semantic Indexing via Singular Value Decomposition

As described above, the most basic result of the initial indexing of words found in the input documents is a frequency table with simple counts, i.e., the number of times that different words occur in each input document. Usually, we would transform those raw counts to indices that better reflect the (relative) “importance” of words and/or their semantic specificity in the context of the set of input documents (see the discussion of inverse document frequencies, above).

A common analytic tool for interpreting the “meaning” or “semantic space” described by the words that were extracted, and hence by the documents that were analyzed, is to create a mapping of the word and documents into a common space, computed from the word frequencies or transformed word frequencies (e.g., inverse document frequencies). In general, here is how it works:

Suppose you indexed a collection of customer reviews of their new automobiles (e.g., for different makes and models). You may find that every time a review includes the word “gas-mileage,” it also includes the term “economy.” Further, when reports include the word “reliability” they also include the term “defects” (e.g., make reference to “no defects”). However, there is no consistent pattern regarding the use of the terms “economy” and “reliability,” i.e., some documents include either one or both. In other words, these four words “gas-mileage” and “economy,” and “reliability” and “defects,” describe two independent dimensions – the first having to do with the overall operating cost of the vehicle, the other with the quality and workmanship. The idea of latent semantic indexing is to identify such underlying dimensions (of “meaning”), into which the words and documents can be mapped. As a result, we may identify the underlying (latent) themes described or discussed in the input documents, and also identify the documents that mostly deal with economy, reliability, or both. Hence, we want to map the extracted words or terms and input documents into a common latent semantic space.

Singular value decomposition. The use of singular value decomposition in order to extract a common space for the variables and cases (observations) is used in various statistical techniques, most notably in Correspondence Analysis. The technique is also closely related to Principal Components Analysis and Factor Analysis. In general, the purpose of this technique is to reduce the overall dimensionality of the input matrix (number of input documents by number of extracted words) to a lower-dimensional space, where each consecutive dimension represents the largest degree of variability (between words and documents) possible. Ideally, you might identify the two or three most salient dimensions, accounting for most of the variability (differences) between the words and documents and, hence, identify the latent semantic space that organizes the words and documents in the analysis. In some way, once such dimensions can be identified, you have extracted the underlying “meaning” of what is contained (discussed, described) in the documents.

Recommended Posts

Data Mining Research Guidance and Thesis Topics

04 Jul 2018 - Data Mining

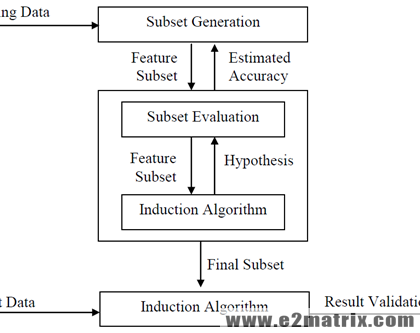

Feature Selection in Data Mining

06 Feb 2018 - Big Data, Data Mining, Machine Learning, Text Mining, Weka

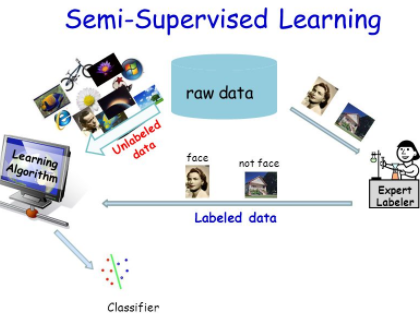

Semi-Supervised Learning Models

25 Jan 2018 - Data Mining, Machine Learning, Text Mining, Weka